Six degrees of Kevin Bacon

You might have heard of actors’ “Bacon number”. It’s a measure of how well-connected they are to Kevin Bacon: if they’ve been in a film with him, they have a Bacon number of 1; if they haven’t been in a film with him, but have been in a film with one of his co-stars, their Bacon number is 2; and so on.

We can model actors’ connections using a *random graph*, where each actor is a vertex, connected to a random subset of the other actors in the system. Using this model, we can look into questions such as:

- Is everyone connected to everyone else, or are there separate clusters?

- What does the shortest path between two randomly-chosen vertices look like?

- Is Kevin Bacon actually the best person to put at the centre?

- Does any of this actually matter in real life? (yes)

</ul>

</p>

</div>

</div> ### Plan: We’ll start by looking at some different models of random graphs, including the Erdős–Rényi and Small Worlds models. From there, we can go in several different directions: we might try to tune the models to better match real-world examples, or think about how random walks/Markov chains on the graphs would look, or use an epidemic model to think about how gossip (or a virus) would spread through the network. ### Prerequisites: For this project, you’ll need to have taken at least one of Markov Chains and Probability II, ideally both if you want to get into the Markov Chains side of it. Discrete Maths is also extremely helpful here. ### Resources: For more discussion of the small-worlds phenomenon and different situations where it’s useful, you could look at Duncan Watts’ books Six Degrees and Small Worlds. (Six Degrees is particularly accessible as it’s written for a general audience). For a more mathematical approach, Random Graph Dynamics by Rick Durrett is a great starting point.

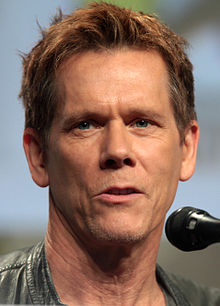

Kevin Bacon: very well-connected